Aviato's Layover

Guide to Narita

Hidden gems, neighbourhood food & quiet walking routes

Explore the guideThe Layover Guide: Narita

Welcome to The Layover Guide! The first in a series of guides to show hidden gems on layovers. Every city has layers most people never see. This series shows the local history, neighbourhood food, quiet walking routes and lesser-known spots that will make your layovers more memorable.

Why We're Making This

Most layovers fall into two patterns: stay in the hotel or open Google Maps and guess. What's missing is something built specifically for crew, structured around realistic time windows and straightforward transport.

This guide isn't an itinerary. It's a breakdown of what's actually in Narita so you can choose what to do based on how much time and energy you have. The goal is simple: Create a guide where you can easily explore, find good food and live life a little more!

How This Guide Works

The goal isn't to turn layovers into sightseeing missions. It's to help you use the time well — whether that means staying close and resetting, or stepping out a little further. If it saves you one wasted afternoon or one stressful train ride, it's doing its job.

Each entry includes some history about the place, what you'll actually find there, and how long each place will take (roughly). There's no required order. You don't need to "complete" a list. Most of Narita's core attractions sit within walking distance of Narita Station and the temple, so you can adjust your plan based on how you feel.

IC Cards: PASMO, Suica & Other Compatible Cards

Japan's rail and bus systems use a rechargeable IC card system similar to an Octopus card. You tap in at the gate, tap out at the exit, and the fare is deducted automatically — this is the same for the buses as well.

In Narita / Tokyo, the most common cards are PASMO and Suica. They are identical and work the same way. However, there are multiple types of IC cards from different parts of Japan which are also compatible:

If you already have one of these from another part of Japan, it will work in Narita.

Mobile Payments & Octopus App

Japan's rail and bus systems only accept local IC cards. IC cards are also useful for buying cheaper items like 7-Eleven drinks and snacks.

If you're coming from Hong Kong with an Octopus card, the physical card itself cannot be used for Japanese public transport or buying items. However, there is now a way to use the Octopus mobile app for payments within Japan through a partnership with Japan's PayPay QR code payment network. This lets you pay at convenience stores, restaurants, shops, taxis and more.

This doesn't replace a Suica/PASMO for transit, but it can make payments in town easier especially for food, shopping and taxis where PayPay QR is available.

History of Narita

Narita officially became a city in 1954, but its identity goes back over a thousand years. The town developed around Naritasan Shinshoji Temple, founded in 940AD during the Heian period. Over centuries it became a major pilgrimage site, particularly during the Edo era (1603–1868), when travellers stopped here before long journeys.

Omotesando, the main street between the station and the temple, formed around that steady flow of pilgrims. Inns, food vendors and specialty shops supported temple traffic, and many of those family-run businesses still operate today.

In the 1960s, Narita changed again with the construction of Narita International Airport. The project faced intense local opposition from farmers whose land was required for runway development. Some refused to sell, and parts of farmland remain inside the airport perimeter today — a rare case of active private land within a major international airport boundary.

Sharing is Caring!

This series is built specifically for crew. If you know someone that finds this kind of stuff interesting, feel free to share it with them. We will be covering more layover cities very soon!

Share This GuideHistorical Attractions

in Narita

Temple and town foundations spanning over a thousand years of history

60–90 min

60–90 minTemple

Naritasan Shinshoji Temple

Founded in 940AD, Naritasan is the reason Narita exists. The temple was established during the Heian period and became a major pilgrimage site during the Edo era (1603–1868), when travellers regularly stopped here before long journeys. It's dedicated to Fudō Myōō, a guardian figure associated with protection and safe passage.

You'll find a large temple complex spread across multiple halls, gates and courtyards. There are also ceremonies that take place at the temple daily.

Early July

Early JulyFestival

Narita Gion Festival

The Narita Gion Festival is one of the largest traditional festivals in the region and has been held for more than 300 years. It is centred around Naritasan Shinshoji Temple and takes place every July. The festival reflects Edo-period community structure, where neighbourhood groups organised and maintained their own decorated floats.

You'll see large wooden floats (dashi) pulled through town, each representing a different district. The floats are multi-tiered, carved and decorated, often with musicians playing traditional instruments on the upper levels.

20–30 min

20–30 minTemple Structure

Great Pagoda of Peace

Completed in 1984, the Great Pagoda of Peace reflects Naritasan's continued growth in the modern era. While much of the temple complex dates back to the Edo period, this structure shows that the institution remains active and expanding.

Inside you'll find Buddhist imagery and exhibits explaining the teachings associated with the temple.

10–15 min

10–15 minGate

Niomon Gate

The Niomon Gate dates back to the Edo period and marks the formal entrance into the temple grounds. Gates like this were built to symbolically separate everyday space from sacred space and often housed guardian statues.

You'll see heavy timber beams, carved detailing and large protective figures positioned on either side. It's one of the more architecturally significant entry points.

10–15 min

10–15 minCultural Property

Three Storied Pagoda

Built in 1712, this pagoda is designated an Important Cultural Property of Japan. It reflects high-level Edo period craftsmanship, particularly in its painted panels and intricate carvings.

Unlike the modern Great Pagoda, this structure represents Naritasan's historical architectural peak. Walk around it to see the exterior panels — most of the detail is on the outside rather than inside.

10–20 min

10–20 minWorship Hall

Komyo-do Hall

Komyodo is one of the central halls within the Naritasan complex and represents earlier phases of temple expansion. It remains an active worship space and predates several of the larger modern structures nearby.

Inside you'll find traditional Buddhist statues and a quieter atmosphere compared to the main hall. It's less crowded and easier to navigate.

~30 min

~30 minCeremony

Goma Fire Ritual

The Goma fire ritual is performed several times a day at Naritasan and has been part of temple practice for centuries. The ceremony involves monks chanting sutras while wooden prayer sticks are burned as offerings.

What you'll experience is a ritual lasting roughly 20–30 minutes. It's open to the public and shows how the temple's religious ceremonies are preserved.

45–60 min

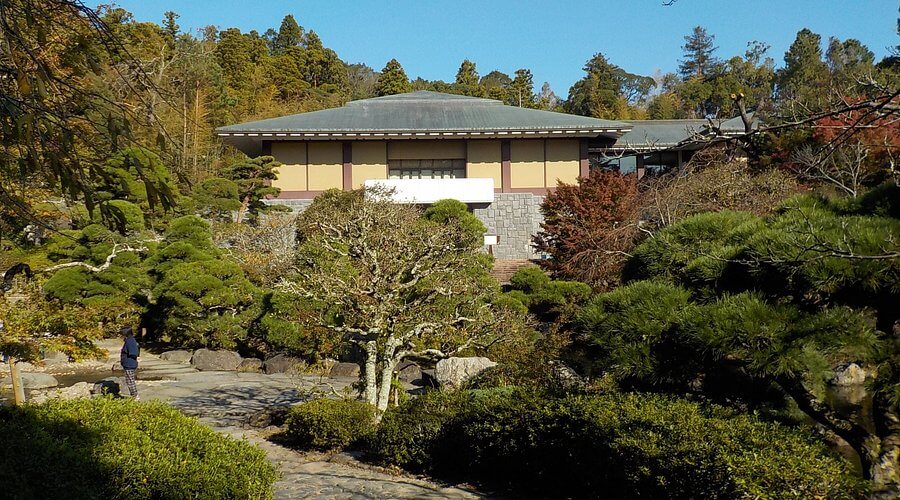

45–60 minMuseum

Naritasan Calligraphy Museum

Located inside Naritasan Park, this museum focuses on the development of Japanese calligraphy across different historical periods. Calligraphy has long been tied to religion, governance and education in Japan.

Inside you'll find rotating exhibitions of classical works and modern interpretations. The building follows traditional design principles and offers a quiet indoor alternative if you want a structured cultural stop.

20–30 min

20–30 minMuseum

Narita Yokan Museum

Narita became known for Yokan, a traditional red bean confection sold to temple visitors. During the Edo period, sweets became part of the pilgrimage economy that supported Omotesando's growth.

The museum explains how the snack was made across different generations. Displays include historic packaging, production tools and records that show how small shops evolved into established family businesses.

~20 min

~20 minInformation

Narita Tourist Pavilion

Located along Omotesando, this tourist pavilion shows how Narita developed as a temple town. It explains how lodging houses, food vendors and specialty shops formed around steady pilgrimage traffic.

Inside you'll find maps, historical photographs and explanatory panels that show the before and after of Narita. It's an interesting way of seeing how the town took shape and grew.

30–60 min

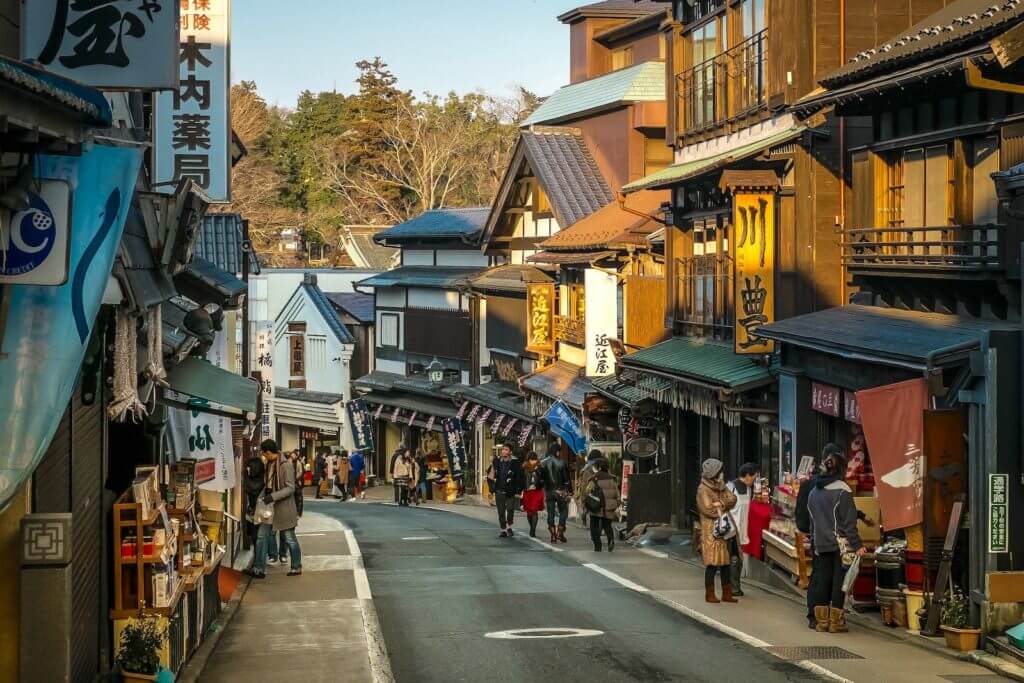

30–60 minStreet

Omotesando

Omotesando served as the approach road for temple visitors during the Edo period. Many of the storefronts along the street have operated for generations, reflecting the town's longstanding commercial identity. You'll see wooden facades, traditional signage and food stalls.

Regional Sites

Short trips beyond town — within roughly one hour of Narita

60–90 min

60–90 minHeritage

Sakura Samurai Residences

Sakura functioned as a castle town during the Edo period, when regional domains were governed under the Tokugawa shogunate. Samurai families lived in designated districts close to administrative centres, reflecting the rigid social hierarchy of the time.

What you'll find are preserved residences with earthen walls, gated entrances and tatami interiors. Some houses display armour and household artefacts, giving a sense of how mid-ranking samurai used to live.

30–45 min

30–45 minRuins

Sakura Castle Ruins

Sakura Castle was established in the early 17th century and served as the administrative centre for the surrounding domain. Although the main structures no longer stand, the site played an important role in regional governance under feudal rule.

Today you'll find open parkland with stone foundations marking where the castle once stood.

2–3 hours

2–3 hoursDistrict

Sawara Historic District

Sawara developed as a prosperous river port during the Edo period, benefiting from its location along the Tone River system. Goods moved between this region and Edo (Tokyo), supporting a strong merchant class.

What remains are canal-side warehouses, wooden shopfronts and narrow streets reflecting commercial planning from the 17th and 18th centuries. It's compact and easy to explore without a fixed route.

60–90 min

60–90 minShrine

Katori Shrine

Katori Shrine is one of the oldest Shinto shrines in eastern Japan and historically held influence across multiple provinces. It was closely associated with martial traditions and samurai culture, particularly during medieval periods.

You'll find a structured shrine complex set within wooded grounds. The main hall and surrounding buildings reflect centuries of reconstruction and continued religious importance.

2–3 hours

2–3 hoursOpen-Air Museum

Boso No Mura

Bosono Mura is an open-air museum that reconstructs Edo period buildings using documented architectural records from across Chiba Prefecture. It was developed to preserve traditional structures that were disappearing during modernisation.

You'll walk through recreated merchant houses, samurai residences and rural farm dwellings. The layout lets you move between social classes and occupations in a controlled setting.

30–45 min

30–45 minArchaeological Site

Ryukakuji Temple Ruins

Dating back to the 7th–8th century, Ryukakuji reflects early Buddhist expansion into eastern Japan during the Asuka and Nara periods. It predates Naritasan and represents an earlier phase of religious development in the region.

What remains are stone foundations and archaeological markers rather than standing buildings. It's a quiet site that provides context rather than spectacle.

60–90 min

60–90 minMuseum

Shibayama Kofun Haniwa Museum

This museum focuses on the Kofun period (3rd–6th century), when large burial mounds were constructed for regional elites. Clay figures known as haniwa were placed around tombs as part of funerary practice.

Inside you'll find excavated artefacts and reconstructed displays explaining how these burial sites were structured. It provides insight into the region long before temple or feudal governance.

60–90 min

60–90 minMuseum

Chiba Prefectural Boso Museum

The Boso Museum covers regional archaeology, political administration and cultural development across different historical periods. It ties together prehistoric settlement, feudal governance and agricultural expansion.

Exhibits are structured chronologically, making it easy to understand how the area evolved from ancient settlements to Edo period domain management.

30–60 min

30–60 minWaterway

Tone River Canal Systems

The Tone River system was central to agriculture and trade during the Edo period. Large-scale engineering redirected waterways to support irrigation and improve transport routes to Edo.

Today you'll see controlled riverbanks, canals and flood management systems that took centuries of hydraulic planning. It's less about a single attraction and more of a nice walk. The river passes by interesting small towns and various historical sites.

30–45 min

30–45 minHeritage

Old Sawara Merchant Warehouses

These warehouses were built during Sawara's peak as a riverport trading centre. Merchants stored rice, textiles and goods transported along the Tone River.

What you'll see are timber structures with thick walls designed for storage and climate control. Many are still around scattered along the canal.

45–60 min

45–60 minBrewery

Nabedana Sake Brewery

Founded in the 17th century, Nabedana is one of the oldest breweries in Chiba Prefecture. It has operated through the Edo period and into the modern era, maintaining traditional brewing methods tied to regional rice production and local water sources.

You'll find wooden brewery buildings housing fermentation tanks and storage areas. When tours are available, they explain how rice polishing ratios, seasonal brewing cycles and water mineral content influence flavour development. There is also a tasting portion included in the tour.

Nature

Walkable outdoor spaces, parks and a natural hot spring

30–60 min

30–60 minPark

Naritasan Park Loop

Naritasan Park was developed in the early 20th century to complement the temple complex and provide structured walking space for visitors. It covers roughly 16 hectares and connects directly to the main temple grounds.

You'll find ponds, small bridges, wooded paths and elevated viewpoints. The layout is clear and easy to follow without needing a map.

45–60 min

45–60 minLake

Lake Inba-numa

Lake Inbanuma is part of a broader wetland system that was engineered during the Edo period to support irrigation and rice cultivation. Large-scale water management projects reshaped the area to improve agriculture and trade access.

Today it's nice walking paths with wide views across the water. It's flat, easy terrain and shows off the region's agricultural foundation.

45–60 min

45–60 minPark

Sakura Furusato Square

Sakura Furusato Square sits along Lake Inbanuma and reflects the region's agricultural planning history. The surrounding land was historically managed for rice production, while the modern windmill reflects Sakura's sister city relationship with the Netherlands.

You'll find open lakeside paths and seasonal flower fields, particularly tulips in April and cosmos in October.

45–60 min

45–60 minWetland Park

Suigo Sawara Ayame Park

Located within the Tone River marshland system, this park reflects the waterways that supported regional trade and farming. During the Edo period, river systems were central to moving goods between towns.

You'll walk along raised boardwalks across wetlands and canals. The park is best known for iris blooms in June, but outside the bloom season it's still a nice and easy loop that doesn't get too crowded.

60–90 min+

60–90 min+Beach

Kujukuri Beach

Kujukuri Beach stretches roughly 60–66 kilometres along the Pacific coast and has historically supported fishing communities. Coastal trade routes and small-scale fisheries shaped the economy of this area long before modern transport.

You'll find open coastline and broad sandy stretches. There's no structured route, and more often than not it's pretty empty.

20–30 min

20–30 minPark

Kuriyama Park

Kuriyama Park is a small green space near Narita Station. It's not historically significant, but it functions as a local reset point within walking distance of town.

You'll find basic walking paths, benches and open lawn space. It's nice if you want a quick breath of fresh air.

30–45 min

30–45 minWalk

Sakura River Canal Walks

Smaller waterways around Sakura and Sawara once supported goods transport connected to the Tone River network. These canals were part of the infrastructure that enabled merchant towns to develop.

You'll find small boats ferrying people and goods, like they used to do back in the day. It's compact and easy to combine with nearby historical districts.

Onsen

Yamato no Yu (大和の湯), Natural Hot Spring

Yamato no Yu is the closest full onsen-style facility to Narita offering natural hot spring water. Located in nearby Inzai City, it draws mineral water from underground sources and operates as a day-use bathhouse.

Inside you'll find separate male and female bathing areas with indoor hot baths, outdoor baths, sauna and cold plunge. The outdoor bath overlooks the open zen countryside.

Food

Authentic Japanese dining — from Narita's famous unagi to quick ramen stops

Unagi

Kawatoyo Honten

Established in 1910, Kawatoyo is one of Narita's most recognised unagi (eel) restaurants. Narita's eel tradition dates back to the Edo period. You'll see eel prepared and skewered near the entrance before it's grilled and glazed in stages.

Unagi

Surugaya

Another well-known eel restaurant along Omotesando, known for a slightly quieter setting. Grilled eel served over rice with sauce layered during cooking. Traditional atmosphere and less crowded.

Unagi

Kikuya

A more casual approach to Narita's eel tradition. Less formal and often faster to get seated. Classic unagidon (eel over rice) without the long wait.

Sushi

Sushidokoro Tsuchiya

A traditional sushi counter. Because Narita sits near the coast, many sushi spots source their fish daily. Small counter setup, direct service from chefs, and classic nigiri.

Sushi

Narita Edokko Sushi

A longstanding presence reflecting traditional Edomae-style sushi. Reliable and locally known. Full menu, set meals and counter seating.

Ramen

Ramen Bayashi

A small local ramen shop near Narita Station. Classic broth styles and quick service — the Japanese version of Maccas. Counter seating and quick food.

Ramen

Hakata Ittenmon

Specialises in tonkotsu-style ramen from Fukuoka. Rich pork-based broth, thin noodles and a compact interior. Fast service.

Airport Dining

Dashi Chazuke En

Located inside the airport, this restaurant serves chazuke — rice topped with ingredients and finished with hot broth. A traditional comfort dish often eaten as a light meal.

Airport Dining

Tempura Nihonbashi Tamai

Classic tempura prepared in the Edo style. While located inside the airport, it still has a traditional menu built around seafood and seasonal vegetables. Counter seating and plated set meals.

Izakaya

Torihan Uohan

A local izakaya serving grilled meats, seafood and small plates. Izakaya culture reflects Japan's after-work dining structure — casual, shared dishes, and drinks. Relaxed atmosphere and less formal.